Nicholas Le Messurier, master mariner

The siege of San Sebastian

|

Diaries

In December 1932 Mr J W du Pre of Southampton placed at my disposal two manuscript books containing the diary of Nicholas Le Messurier and from these books I extracted sufficient matter to write an article in the Jersey Evening Post of 22 December 1932. When the article appeared I received a message from Mr Woodcock, of the Analyst department of the Jersey States, telling me that he had a third book containing additional matter to that contained in the article, and, as he subsequently generously presented this third volume to La Société Jersiaise, it was decided that it would be of some interest if I gave a paper on the subject of these diaries before the members of the Society.

The three volumes contain a full account of the 29 voyages made by this master mariner during the long period he followed a seafaring life. Some of these voyages only lasted a few months but on others he was absent from his home port for nearly two years. It gives us a very graphic picture of a sailor's life in those days when the master of a vessel had very strong ideas on the question of discipline and the mate and boatswain were often selected for their physical and vocal efficiency.

Food was often bad, water scarce, there were no Board of Trade regulations and very often the ordinary sailorman suffered from the actions of a mean owner and a brutal master. Everything depended on the owner of the vessel, as if the master failed to make a vessel pay, there were always plenty of others who were only too anxious to step into his shoes. Boys in those days went to sea at a very early age and those who survived and managed to reach above the ordinary sailor's lot, were generally recognised as good sailors, ready to dare any danger, face any hardships and they saw no reason why the system under which they had learned their trade should not be carried on.

Some of us can remember the loud voiced mahogany coloured mariner who could not get away from the idea that he was shouting his orders from the quarter deck of his vessel. Brave sailors, good navigators, hard swearers and hard livers but still God fearing men who were full of the mysteries of the sea. At every port there were certain parlours where ship masters congregated, smoked their churchwardens, drank their favourite beverage and told their stories about what they had done and what they proposed to do.

Masters and traders

In those days they were not only masters, but traders and therefore there was a kind of freemasonry among them and, except when the question of sailing qualifications of their several vessels was discussed, they were always ready to help each other in carrying out their voyages or sometimes in throwing dust into the eyes of their owners. They were adventurers who started on a skeleton voyage but filled in the gaps as trade allowed. Some of these masters were clever business men who, after they left the sea, became the founders of big shipping companies.

Guernsey birth

We learn that Nicholas Le Messurier was born on 11 September 1801 and was the son of Abraham Le Messurier of Back Street, St Peter Port, Guernsey and Rachel Le Provost of Les Provosts in the parish of St Saviour, Guernsey.

In those days there were no schools nor other restrictions and therefore, as it was determined to make him a sailor, his parents, taking advantage of his uncle and godfather being in command of the Brig Brothers of Guernsey, sent him to sea on 14 March 1813, when young Nicholas was 11½ years old. He was shipped on board this vessel as apprentice and sailed from Guernsey for St John's, Newfoundland on the same day.

The voyage outwards was very stormy but on arrival there they loaded codfish for Corona in Spain and sailed from St John's on 10 June 1813. But unfortunately the vessel never reached her destination, for on 20 June she was attacked by an American privateer called America, of the Port of Salem, carrying 20 guns and 180 men. Although the Brothers put up a certain resistance, she was captured by the Americans. The Brothers carried ten guns and 19 men and had been granted a letter of Marque.

Young Le Messurier thus started an adventurous career at a very early age, for the Americans placed on board the Guernsey brig a prize crew of nine men and left on the Brothers the master and the two apprentices. They set sail for Bayonne but on the way HMS Surveillante (Captain Collier) hove in sight and chased the Brothers so that the master sought shelter under the French flag in a Spanish Bay and, thinking they were safe in French waters, they hoisted a flag for a pilot.

Unfortunately for the Americans, the port was Fuenterrabia, which five days previously had been captured from the French by English troops. In reply to their signal, a launch came from the shore manned by 20 men and the prize master and Captain Le Messurier were taken ashore to be examined by the officer commanding the district. The commandant then sent 50 soldiers to guard the vessel and next day a crew of sailors were sent on board, and sailed the vessel to Passages, where the Americans were detained as prisoners of war and Captain Le Messurier and his two apprentices were set at liberty.

To add to the chagrin of the Americans, when night came on, they could see the lights of St Jean de Luz in the distance. The Brothers was then fitted up as a small man of war but after two or three voyages was wrecked.

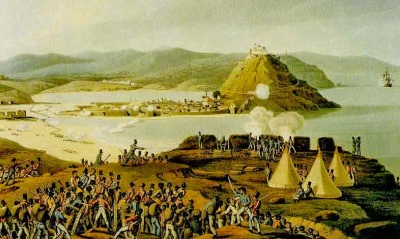

Siege of San Sebastian

Young Le Messurier spent three months in Passages during which time he witnessed the siege and capture of San Sebastian. In his diary he tells us of the marching of the soldiers, the bombardment of the port, the soldiers fighting their way into the breaches, the wholesale burning of the slain; indeed he saw "more than I can describe, suffice it to say it was a bloody action". San Sebastian was taken on 9 September and the garrison of 1,300 French troops was made prisoners of war.

During his stay in Passages the schooner Falcon of Guernsey, with codfish rom Newfoundland, had been captured by an American privateer but the Americans had made a similar mistake in thinking that they were in French waters, and the English and Spaniards turned their guns on the vessel and sank her.

At last the Courier of Jersey, Captain Clements, arrived with a cargo of provisions on a speculative voyage and having sold the cargo to great advantage, Captain Clements offered young Le Messurier a passage to Jersey in his vessel. On arrival there he sailed for Guernsey in the Prince de Bouillon and reached there after a very eventful seven months absence from his home. Thus ended the first of his 29 voyages at sea - a very varied and eventful experience for a boy of 12.

On 8 June 1814, his uncle having been appointed master of the schooner, Pilot of Guernsey, (one of the prizes made by the privateer Vittoria) young Le Messurier commenced his second voyage. They joined the East Indian convoy under HMS Cumberland, 74 guns, and sailed for Madeira. They arrived there after a pleasant voyage but as they were unable to sell their cargo, consisting principally of prize goods, they visited Rio de Janeiro, Cayenne, St Bartholomew and St Kitts, where Captain Le Messurier not only managed to sell his cargo but also his ship to advantage. He bought a brig called the Jane, loaded her with rum, molasses, indigo, etc. and sailed for Guernsey where she arrived on 9 May 1815.

Antelope

On 5 June young Le Messurier sailed with his uncle in the Brig Antelope of Guernsey, 267 tons, belonging to Messrs Priaulx Bros, and after loading a cargo of cod from St John's sailed for the Mediterranean, took a cargo of wine for St Salvador, and then sugar and tobacco for Guernsey where they arrived on 1 July 1816. He was then promoted to be an ordinary seaman and joined the ship Race Horse of Guernsey on 22 December 1817, with Captain Peter de Garris as master. During the second voyage in the Race Horse they sailed from Guernsey with 133 passengers for Baltimore where they arrived after nine weeks passage and landed all the passengers "except of a child which died and was committed to the deep within sight of the Bermuda Islands".

On the third voyage in the ship Race Horse, after unloading a cargo of wine at Trinidad, in Cuba the ship got aground at the entrance of Porto Casilda; after lightening the vessel and getting a pilot on board, the Race Horse was boarded by a pirate boat under the Mexican flag and, after the pirates had taken off the pilot, who was probably one of them, the provisions and what they fancied, the crew of the Race Horse were left to get into port the best way they could.

When they arrived in port they found that the people were in a great state of fear and excitement on account of the action of this pirate vessel and all trade was being stopped in consequence. So it was decided to fit out a Droger with a gun and man it with 45 men collected from the shipping in the port and put an end to this annoyance to the shipping. Four men from the Race Horse volunteered for the expedition for which they were paid eight dollars bounty and prize money.

Droger soon came in sight of the pirate and having fought and captured her, the crew of 14 pirates were brought into Casilda as prisoners, to the great joy of the people, who pelted them with mud and stones as they wended their weary way up to the jail.

Lightning strike

On 3 April 1820, Easter Sunday, as the vessel was sailing out of the Gulf of Florida, she was struck by lightning, "the electric fluid striking first the iron spindle for vane at the masthead and shattered the foretop gallant mast like a broom, came down and took the parcelling off the top mast backstays, cut several ropes and blocks and entered the forepart of the foremast through an oak fish which was bound to the foremast by iron hoops, close under the heel of the topmast; it descended down in the mast and came out on the after part of the mast ten feet above the deck, it then rose up and went through the clue of the foresail which was clewed up and fell over¬board to the starboard bow."

Captain de Garris declared that he saw the fluid enter the water and a drop of iron was hanging to the pin of sheave for halyards. All the crew were more or less electrified by the shock and some thrown off their legs, but after clearing up the decks and fixing new rigging they continued the voyage.

But evidently the Race Horse had been strained by the shock for a few months later, when on a voyage to Havanna, she sprang a leak and notwithstanding incessant pumping, the water increased and the crew were fortunate enough to signal to the American schooner Active, which took them aboard just in time to see the Race Horse disappear under the water.

They were taken to Malaga where Captain Philip Malzard of the schooner Betsy of Jersey gave the shipwrecked crew a passage to Plymouth and young Le Messurier arrived home in Guernsey on 14 March 1821.

He was now 20 years of age and had had considerable experience of the sea; therefore it is not surprising to see this experienced navigator as mate of the cutter, George IV of Guernsey, 112 tons, belonging to Wm Jones and Co. He remained in the vessel until March 1822, when he joined the ship Reward of Guernsey, belonging to Messrs Sheppard, Symes and Co, and he remained in this vessel until 19 November 1825, after serving in her for three and a half years. On 23 November 1824 at 4 am when off Guernsey, it came on a hurricane and taking in the storm sails, the captain let her drive under bare poles. "The sea was extraordinary smooth by the violence of the wind, sea gulls alongside had no power to raise out of the water and the vessel was laying over very much with part of her deck cargo under water; indeed it was feared she would have blown over and I thought it was all over with us."

However the vessel weathered the storm but it discouraged the mate, Mr Agnew, from continuing a sea life and, getting a post in a bank, he died in 1852 as manager of the Guernsey Commercial Bank.

Princess Charlotte

Le Messurier sailed as mate in the brig Princess Charlotte of Guernsey, 174 tons on 1 January 1826 and obtained his discharge on 4 November after having been detained against his will. "For I begged him to let me go the first passage at Havanna he would not and has tormented me these ten months he was a great tyrant indeed I may say that I jumped from the frying pan into the fire in joining as a passenger the Union of Guernsey, at Rio de Janeiro and arrived in Guernsey on 29 January 1827 after a passage of 85 days which might have been performed by any enterprising person in 65 days."

On 25 March 1827, Messrs Hannibal Sheppard, Aaron Stark Symes, and Hillary Evans Jeffreys bought a brig on the stocks from Mr John Vaudin and young Le Messurier was selected to see that the vessel was properly rigged and appointed. She was launched on 11 May 1827 and, much beyond his expectations, the young sailor was appointed master. The vessel was named the Flora, 158 tons, and he remained in the vessel as master for 12 years and 4 months.

Flora

On 29 May 1827 the Flora sailed for the Cape Verd Island Mayo, to purchase and load with all possible speed "a cargo of good salt on the most advantageous terms on barter for some of the goods you have on board," provisions, cordage, sail cloth, shoes etc and proceed to Monte Video where Messrs Bertram, Le Breton and Company would give further orders.

On arrival at that port on 24 October the master found to his cost that the agents would take no responsibility and the young master, anxious to make good on his first voyage in command, fretted considerably and pointed out to his owners that the agents "sometimes speak about a loading on your account and sometimes about a freight and so the days slip by". There were two guards on board the vessel, one from the Custom House and one from the Fort and whilst waiting he had trouble with his crew, as three of them when under the influence of drink went on board HMS Beagle, and joined the Navy.

It was no use protesting in those days, for the Naval Office was all powerful and any sailor was at liberty to leave merchant service and join a Naval vessel. But Le Messurier consoled himself with the reflection that the men he had lost were lazy fellows and when they had drink, they were very quarrelsome and created great uproar on board.

He had a sample of their conduct as they left the vessel for they used foul language and told the master that he was nothing but a damned drunken swab, which so upset him that he seized the first thing he could lay hold of, a handspike, and chased them round the deck, but they managed to escape into the forecastle before he could hurt them.

In reporting the matter to his owners, Le Messurier expresses his surprise that the Navy should be allowed to "take men in this manner to distress them" and he assures the owners that it "was not by being too severe, too cruel, nor pinching their bellies that these men should have wished to leave the vessel, but it is an old saying that a scabby sheep mars the whole flock." He also expresses regret that times had altered since he first went to sea when the master was allowed to punish the members of his crew as he saw fit, but "now he had always the fear of being brought before justice."

Total control

The correspondence between Le Messurier and his owners during the next 12 years gives a good sidelight on the conditions of the life of a master mariner of those days. He was not only the sailing master of the vessel but he acted as the ship's agent as well; for although at certain ports there were accredited agents, yet the delays and difficulties in getting in touch with the owners compelled the latter to place in the hands of the master all control over the movements of their vessels when in foreign waters.

He had many means of making money on his own account by commission etc, but generally he saw that it was to his own advantage to do the best in the interest of his owners. Nowadays we often hear of the blame of disaster, through not complying with the regulations, being placed on the shoulders of a master, but he is well aware that if the vessel does not keep time, the owners are always able to find someone who thinks he can do so.

Masters in those days were not only expert navigators but had to understand and take advantage of the different rates of exchange, study market prices, buy in the best market and carry the goods to a port where such commodities were required and could fetch a good price. The owners were fully aware that the master could study his own as well as their interests and therefore it was no unusual thing for a master to acquire a share in the vessel he commanded as well as certain space where he could carry goods of his own special enterprise. Wages in those days were very low - from six pounds a month for the captain to fifteen shillings a month to the boy - but many Channel Island captains did well and laid the foundation of the good fortune which their descendants enjoy to this day.

Life on board ship was anything but pleasant and there were no Board of Trade regulations in those days as to load line, provisions, manning or accommodation. The provisions were often of the vilest quality bought in the cheapest market and quite unfit for food, and the water was often very bad. But generally speaking the manning was sufficient, for in the little brig Flora of 158 tons, the crew consisted of Master, two mates, carpenter, cook, four seamen and a boy. Le Messurier complains, however, that the mate was an old master who was partly blind and of little use.

Once on board a vessel the sailor knew that he was in the power of the master and mate, who, if decent men, could depend upon a contented crew, but, if otherwise, could make the lives of their subordinates a little hell on earth. The only fear they had was mutiny, and then that only took place when the sailors deemed it worth their while to risk their lives in order to escape from the bondage under which they lived. In passing Gibraltar it was in those days necessary to obtain a pass against Algerian molestation and we often read of passing vessels warning each other about the whereabouts of Algerian pirates.

Le Messurier's letters to his owners are very interesting and describe why he had done such and such a thing, the difficulties of obtaining a cargo, the weather, and the numerous delays caused by the number of fast and feast days when no work was done. He carried hides from South America, and had to be careful that the bales were not full of worms, coffee and sugar.

Wine tasting

When loading wine from Portugal. Spain or Trieste, the owners warn him to see that the wine is full bodied and rich in colour and fortified with strong spirit so as to suit the South American palate, and he is directed to taste each cask taken on board so that he shall not be defrauded by the exporters. He tells the owners that the vessel is swarming with mice, but as it is too expensive to smoke out the hold, he has bought a cat at Gibraltar which has killed many.

He much dislikes going to Havannah, where there is always yellow fever, and he tells how the ship alongside had lost the captain and three men and that one ship in the bay had only a boy in charge, all the rest of the crew having died.

He saw very little of his home whilst in the Flora, as the vessel was kept going, but the owners kept him advised of the health of his family. We can well imagine his anxiety when he saw in a Guernsey paper of March 1833 that there were 351 cases of Cholera in Guernsey and that 97 had proved fatal.

Sometimes the owners complained about the delays and expenses and Le Messurier replies that he has been as economical as possible. "I have pinched both myself and the crew these last two passages by not having sufficient on board and that gives me great uneasiness."

Later on he resents the suggestion of extravagance and explains that in their interest he has acquired the reputation of starving his men, but that for extravagance - "I do not run into wild or unnecessary expenses. Four days in six months have I been free from sea and quarantine I cannot get very wild in so short a time. Six pounds a month will not allow a man of any sense to be wild or extravagant."

Comparisons of pay

He then takes advantage to explain the difference in pay between a captain from England or Jersey and himself. English Captains were paid £9 9s a month, half commission etc and 25s a week extra when in port, and Jersey wages ranged from £100 to £120 per annum. Then he complains that other ships get six dozen wine sent on board for the captain's use, but that he has to buy his own wine. But at the end he winds up by saying that he is willing to sacrifice his life in their service and that "was I even to know of my dismissal on arrival at Guernsey, the world never lessens my exertions for your interest to the last."

He tells of storms, contrary or no winds, damage to the vessel and meeting of other vessels from the Channel Islands. In our everyday life we often hear of our friends describing how the tactful steward had assured them that the crossing they had recently made had been the roughest passage they had ever experienced. Such tactful conduct on the part of the steward enabled the passengers to forget their recent discomfort and revel in the admiration and sympathy of their friends.

Hurricane

But when off Sardinia, on 14 February 1838, the Flora met the real thing when the wind was blowing a hurricane from the WNW and the seas were up to a tremendous height and were threatening to swamp the vessel every moment. Le Messurier tried to lighten the vessel by throwing her guns overboard, starting the water casks but failed to get at the cargo. The main topsail was blown away and the foretop mast staysail split into ribbons, the jib got loose on the boom and three men rushed to secure it, but were washed overboard, two being saved by a rebound back sea but the third was drowned.

The caboose house and the lee bulwarks were carried away and all the water casks washed overboard and the long boat damaged. Le Messurier expected every sea to "swallow us up and I left the whole to Almighty God to decide our fate". One heavy sea struck the bow of the vessel and lifted the bow so high that the stern was driven deep in the water and the jolly boat stove in. The bowsprit was badly sprung. Fortunately when all hope seemed gone, the wind veered to NW and the vessel was better able to bear on to the seas.

"I must say it was a miracle and nothing more than the goodness of the Almighty which has preserved us to give an account of that awful night - never have I seen such heavy seas before." Finally the Flora reached Trieste in a shattered condition.

Quarantine in those days at foreign ports often depended on the whim of some important official who had the power to delay a vessel for weeks at a time and vessels were often sent to distant places for the purpose.

Lily

There are other stories and episodes mentioned in these interesting diaries but sufficient has been given to let us have an idea of the life of a seafaring man of those days. Le Messurier became part owner and master of a new brig called the Lily of Guernsey, 162 tons, which cost £3,074 of which "I unfortunately took one quarter part". Fortunately he was appointed Deputy Harbourmaster of St Peter Port in 1849 and Harbour Master in 1859. He resigned the appointment in 1866 and died on 15 October 1877. For some years he had suffered from a series of rheumatic attacks.

I do not think there is a better finish to this paper than by quoting from the Guernsey Comet of 17 October 1877.

- "He exacted the respect due to his position. By some he was considered stern, really he was not so. His apparent inflexibility was derived from the training at sea to which men were compelled to submit half a century ago. It was hard in its character, yet from a similar course of education - if education it may be called - rose to eminence many who, in that day and generation did good service to their sovereign and country. Captain Le Messurier was a trusted servant when in command of a vessel and he retained to the last moment of his official life the confidence of the authorities."